Pete Owen’s head floats in the middle of my laptop screen, enclosed by the room he sits in and by an abundance of

various, virtual windows dangling around him. My own head, a lot smaller and framed by my personal window, hugs the

right of the screen. Further out a desktop picture is peeking through gaps in windows: it is a NASA photograph of the

sky, with a multitude of stars suspended in the light, velvety indigo blue. It’s breathtaking.

The screen hovers in front of me, against a plain, white wall. The dimensions of the screen are 12 inches by 9 inches -

or 15 inches diagonally; it could be a miniature landscape, hanging on the wall. Pete and I greet each other and talk a

little bit about how weird this new world of online meetings feels. Then I ask: So, how did it all start with City

Racing? Well, in a nutshell

Pete answers, me and my friend Keith decided to put on a show in his studio in 1988,

just as a one-off, and it gradually grew into a bigger group over the next year. And it grew from there; there was no

big plan. We managed to run it for the next nine years. It seems a bit weird to think now, how did we manage to do

that? 1

We both laugh at the impossibility of that task, or maybe at the unlikelihood of having cheap space, or any

space, in London today.

City Racing was an artist-run gallery space, active between 1988 and 1998, housed in the biggest squat in London at the

time: Oval Mansions in Kennington. It was a collaborative work between Pete Owen, Keith Coventry, Matt Hale, Paul Noble

and John Burgess, and throughout its time it held exhibitions by a mixture of artists, including Gillian Wearing,

Michael Landy, Brian Griffiths, Fiona Banner, Peter Doig, Sarah Lucas, and many others. Initially, in the 1880s, Oval

Mansions were a home to the employees of a company that "built and ran gasometers just behind the Mansions"2. Houses were

later divided into council flats, only to be "condemned in the late 70s"3. The first squatters moved in in 1983, into

the barely functional building with no hot water, no electricity and no heating.

Each room was a home. A time of beef

tea, non-tipped cigarettes and soap made from boiled animal bones. This atmosphere still prevailed. 4

The first, two-man

show was in Keith’s studio, number 58 Oval Mansions. It was a former betting shop and the green, perspex sign stayed at

the front, with its hand-cut lettering, affirming: City Racing.

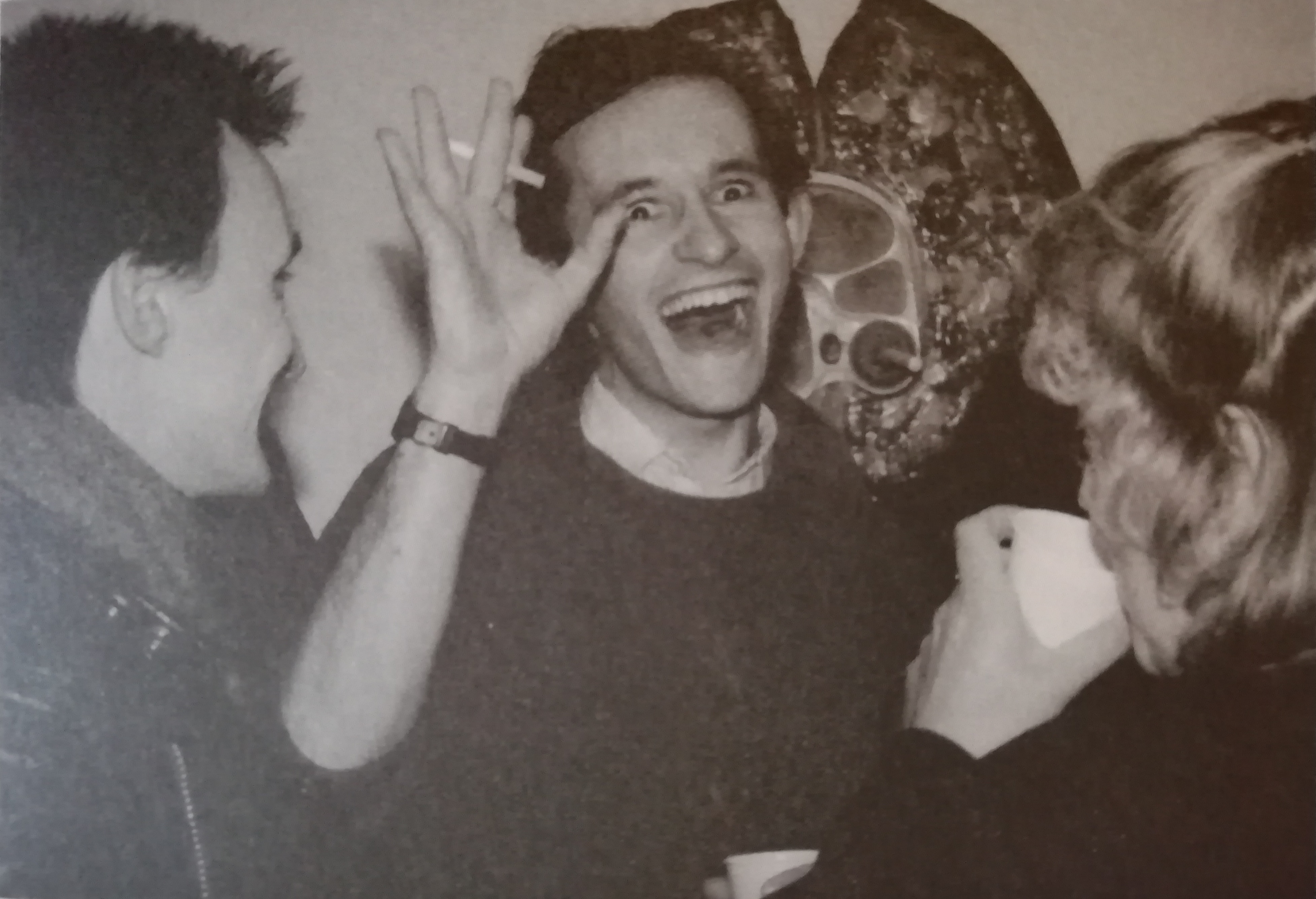

We did about fifty shows and it was a major part of my life!

Pete says, still somewhat surprised. He shows me a book

they’ve put together and published four years after the gallery closed its doors for good. It’s titled City Racing. The

Life and Times of an Artist Run Gallery. Pete smiles at a photograph in the book, which he then shows me through his

computer’s camera, which I then try to decipher on my laptop’s screen. I manage to glimpse just a fraction of it, the

rest is cut off by various windows and the motion of Pete’s hand, but I can’t shake off a strange feeling of peeking

into the past, into a tunnel framed by various lenses, or a keyhole I have to put my eye against. I feel slightly motion

sick: is this what time travel feels like? Or is this sinking feeling a failure to establish the horizon in front of me?

A week after our online meeting, the City Racing book arrives in the post, with a handwritten note from Pete. I

curiously flick through pages, filled with photographs and written stories, before unwittingly burying my face in pages

and inhaling deeply. The smell of fresh, printed paper is heady and resembles emulsion paint. Pages are thick, smooth

and cold under my fingers; they are white walls in this space between the two covers. Here, photographs and artworks are

curated, and stories are organised into exhibitions. I’m holding this space between my hands and it feels like a perfect

extension of the City Racing gallery: photographs hang on pages, gridded and framed by the writing. The fragmented space

also mirrors my online meeting with Pete to some extent: with its windows and borders, and edges, and frames.

A sentence, describing commercial galleries of that time in the introduction to City Racing book grabs my eye: (…) whilst drinking the drinks, showing your face, standing

outside on the pavement making up the numbers in someone else’s scene, it hits you: this gallery will never show your

work. This gallery has nothing to do with you. You’ve got nothing to do with this gallery. (…) Out on the pavement, you

realize that you are surrounded by your own scene. There is only so much room inside, but the good thing is that outside

the space is unlimited. 5

I look up with a gasp: chalky white walls of my bedroom hiss and dissolve into an open, velvety June-blueness.

Space outside the frame in the art gallery setting was first considered in the early 20th century, with the gradual

abstraction of art and a growing interest in light and colour. The term white cube was coined, signifying a perfect

gallery space: pure white, synthetic, shadow-less and well-behaved. Artworks in such space are uninterrupted,

undisturbed and untouched. White walls of the gallery act as frames, making art the foreground and the centre. Brian

O’Doherty writes about the evolution of the white cube space: The ideal gallery subtracts from the artwork all cues

that interfere with the fact that it is "art." The work is isolated from everything that would detract from its own

evaluation of itself. This gives the space a presence possessed by other spaces where conventions are preserved through

the repetition of a closed system of values. Some of the sanctity of the church, the formality of the courtroom, the

mystique of the experimental laboratory joins with chic design to produce a unique chamber of esthetics. So powerful are

the perceptual fields of force within this chamber that once outside it, art can lapse into secular status (…). 6

This

perfect space is something of a spaceship, where the body floats in a zero gravity environment, alienated and

interfering with the surrounding room, The space offers the thought that while eyes and minds are welcome,

space-occupying bodies are not- or are tolerated only as kinesthetic mannequins for further study. This Descartian

paradox is reinforced by one of the icons of our visual culture: the installation shot, sans figures. Here at last the

spectator, oneself, is eliminated. You are there without being there (…) 7

I wonder how that refers to a gallery space that, in the present moment, only exists in memories or a book form. Memories don’t tend to hang on neutral, white walls; they’re loaded with digressions, misthoughts, stutters. They’re inside the human body, constantly digested, ingested and expelled. Mind’s walls are imperfect, they’re antonyms of a white cube space. What happens to an artwork placed and buried deep in human thoughts? Does the constant sound of consciousness somehow change its form, scale, colour? Or is it the mind or body that changes, under the pressure of the artwork?

I put down the essay and my gaze falls ahead of me, unintentionally sticking to the wall ahead of me. The walls of my house are pure, clinical white. They leak sounds from outside, conducting them into the space where my body lies stretched out, absorbing each sound wave with a recoil: city electrotherapy. Sounds vary in their intensity, provenance, irritability and discordance. Some gnash against the white walls of my house and against the white bones of my body; some are piercing and insanity-inducing; some are just background - hissing or swooshing, or humming. My house borders two different worlds: the busy street that connects South and Central London, with sounds of sirens, exhaust pipes and disembodied human and non-human screams, and the open greenery of a park, where parakeets stick to trees and foxes howl just before dawn. Every night these two worlds collapse into each other and bleed sounds from their edges: a wounded, sickly place. Every evening a man sits on a bench bordering the park and the street and plays a flute: the melody is sombre, continuous and abysmal, and if hopelessness had a soundtrack, that would be it. I’m an unframed, foggy landscape; the white walls of the house frame my body in space. This frame is liquid, moveable, aspirin-like: chalky and soluble. My horizon is blurry and uneven. My eye wanders and falls off a cliff. The door slams, I leave the house.

City Racing stood as one of those spaces that didn’t fit the frame, whether that frame was London in the 90s or the frame of the art world. As a gallery housed in a squat, it was outside of the bureaucratic, banking world of London, but as a space that was run and curated by artists, it was also separate from the mainstream, profit-driven art world. It was outside: it was alternative. Artist-run.

It is this terminology that makes the matter very knotty. To fully understand the term “artist-run”, I scour the

Internet for clues. An artist-run space is a gallery facility operated by creators such as painters or sculptors, thus

circumventing the structures of public (government-run) and private galleries. 8

It seems straightforward, but the deeper

I dig the more complex the matter gets. Take City Racing as an example: curation and organisation of their shows were in

the hands of artists, however, funding came directly from Arts Council England; which contradicts the proposed meaning

of the term; artworks were also available to be purchased during shows (Pete recalls during our conversation one of

Sarah Lucas’ pieces sold to Saatchi).

Rebecca Gordon-Nesbitt argues in her essay Surprise Me, published in an exhibition

catalogue Life/Live (which City Racing was part of) in 1996, that contemporary “alternative” spaces operate "outside but

not counter to extant cultures”9, since they rely on pre-established systems of patronage. Since Arts Council England

chooses which project or space to support and which to decline, and a selection of artists-curators have their own

process upon which they decide who will show in their space, and artworks are being sold to collectors, how is

artist-run or alternative space different to a mainstream gallery? Where lies the border that frames this term? Or “to

what extent the alternative is mainstream”10?

Jacqueline Cooke writes, quoting Malcolm Dickson, artist-run space can be “reclaimed as a temporary autonomous zone”

because it is free from the curator as (capitalist) boss but he concludes that there is no longer a clear inside/outside

or centre/periphery either geographically or in roles - the artist initiated project is just as much an institution as

the gallery, its value, he states, will be in being more local, specific to context and place. 11

This makes already murky

borders of the matter even more vague. Differences between the seemingly synonymous terms “alternative” and “artist-run”

are problematic, too. Cooke writes, as she delves into the subject: It is clear that the terms alternative and

artist-run themselves have been sometimes interchangeable, sometimes contested. The term ‘alternative’ implies if not

opposition, at least a context (alternative to what?) and locality is one context. 12

Rebecca Gordon-Nesbitt criticises

the term “alternative”, used by Time-Out, as “a label loaded with dated, anti-Establishment connotations” 13 . Cooke

elaborates on terminology further, During the 1980s, Time Out had listed non-commercial galleries under the heading

‘Fringe’. After 1996, the phrase ‘Upcoming’ was used, a term implying something new and aspirational and reinforcing a

hierarchical view of the gallery system. By 1999 Time Out was listing by geographical area, with the East containing the

largest number of new, shorter-lived and possibly alternative galleries. 14

Despite all of these varied terms being

formulated, “artist-run” or “alternative” seem to have survived and still be in use today.

The main difference between “alternative” or “artist-run” and mainstream spaces appears to be in the way that artist-run

spaces work on a collaborative basis. The spaces (…) he writes about share the originating impulse of the artist space

in providing facilities, interaction, collaborations, putting ideas into action (…). 15

Collaboration and community are at

the core of artist-led projects and were a major part of creating the City Racing gallery, as Pete tells me: People

used to come to our private views and it was a major networking event for many young artists. Space became a meeting

place. That social space was vital to the gallery” 16

What do you require as a space? To make art you don’t need anything kind of fancy… You just need motivation, somewhere

that is dry and reasonably warm… The idea of post-studio is being brought up a lot now because people work on laptops.

You can’t make something big, dirty and smelly on a laptop because it just doesn’t work, does it? 17

City spills like a greasy, fuscous stain, swallowing more and more space with each dirty smear outwards. The engulfed

space shrinks, goes down a dirty drain, or up a tall, glass building, or falls into some businessman’s polished leather

shoe, only to be ingested, to be corrupted. Space bends, flexes and vanishes. City is racing: to possess, consume,

ingest space, always more space.

In 1987 the Tories unveiled a plan to build the M11 Link Road in Leytonstone. The proposed six-lane road would run

straight across several residential roads, Fillebrook Road, Grove Green Road, Dyers Hall Road, Colville Road and

Claremont Road, ripping homes and communities apart.

(…) The roads were to be ploughed through areas of outstanding

beauty, special environmental significance, or built-up communities. The transport efficiency gain over environmental

loss correlation in each of these cases was so slight it was arguable. 18

Leytonstone back in the late 80s was a low-cost

and quiet home to an agglomeration of artists, including Paul Noble, Matt Hale and Pete Owen. To save their

neighbourhood, the residents of Leytonstone combined their forces with the residing artists and started a major

anti-road protest in the early 90s.

We became the STOP THE M11 LINK ROAD CAMPAIGN. A group of artists took time out of

their studios with other transient and long term residents and came together as a community in order to fight the road

and to protect their area. What began as a hindrance to the pleasant hum of E11’s atelier continuum, became a focus for

collective action, education, agitation and demonstration. We were living out some kind of Brechtian experience. Like

Mother Courage, events around us affected how we thought about everything. It was impossible to separate studio life

from the daily demands of protesting. 19

Despite the opposition from residents and artists, the M11 Link Road was soon

conceived, and with its birth, there came the death of houses and communities. The M11 Link Road, being a physical

linkage between two places, also became a split; a force that severed people’s lives in half and drove communities

apart. City expansion is a grimy, outward thrust; it flings open windows in houses and apartments, flooding them with

noise and sooty fumes.

Surviving this constant motion, this anxiety-inducing agitation doesn’t get easier when pushing against the current or

hanging in space, like a foggy landscape. The mooring feeling only happens when one is able to establish a horizon; in

this case, a stable ground of home, of community; the hardness of the pavement outside of the gallery, where “you are

surrounded by your own scene” 20 . You exit the frame and take your art outside, into the world. The lessons we learnt were

simple but easy to miss: life is much more boring without community. Community is easy to find. Being an artist doesn’t

mean that you don’t have to participate in the real world, quite the opposite, the trick is to let the real world

participate in your art.

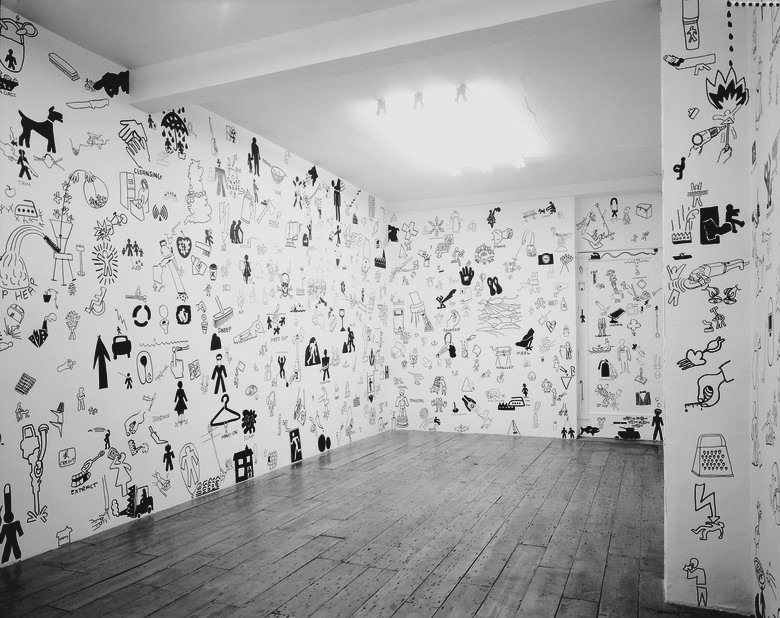

I ask Pete: “You mentioned at one point that in the space there are probably still some remains of the gallery? What did

you mean by that?”

He answers: Oh, there might be! I’ll show you an example of what could be there… Unless they ripped it out completely…

Michael Landy did this, he used marker pen on walls. Obviously it was painted out. But if they didn’t rip the walls out

and just worked over them with paint that would still be there. I’d love to think that that would still be there, or

fragments of it. That thing about the space not existing… It becomes like some sort of a ghost, doesn’t it? 21

Signs? Frescos? Street art? Hieroglyphs? Cave paintings?

The door slams shut behind me. I shuffle my feet a little bit, hoping my shoes are comfortable enough. Nobody is

around:

the city is in a coma and the air is poisonous. All human inhabitants are bearing the burden of this poison: their

faces

only half naked, mouths strapped, suddenly acutely aware of their breath, aware of the empty space in their lungs.

This

city is fucked and it loves space; so it crawls into people’s lungs. I walk on the edges, on concrete and pavement,

on

some grass and dirt; I step into broken glass and a few droplets of blood. On the screen of my mobile phone a

curved,

blue stroke leads the way for my feet. I follow. I cross three parks and fourteen roads. The whole journey takes

about

forty-six minutes.

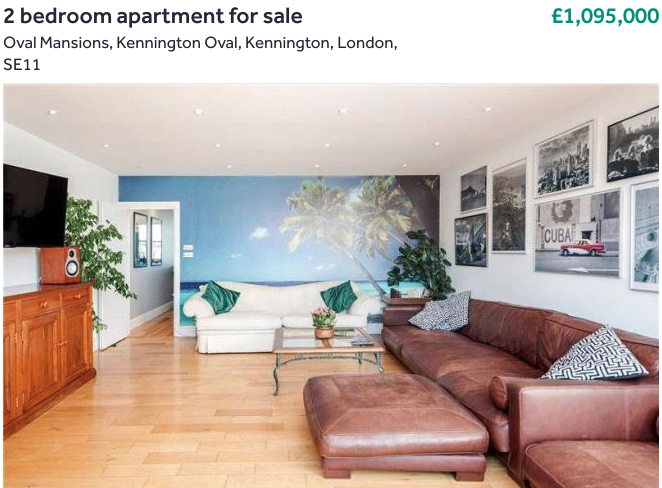

When I get there I can’t enter, obviously. The space doesn’t exist anymore, not in that way and not in the present, at

least. I stand outside on the pavement across the street, taking in the scale of the building, sand-colour brickwork

scraping the blue sky and glaring whiteness of the adjacent building. Windows of the former gallery have thin, white

borders around them. It looks exceptionally normal. Apartments look posh, finished to the highest standard; London’s

biggest squat with its freezing rooms and split pipes in winter is a distant past. I can’t smell any beef cooking in an

iron pot, or any non-tipped cigarettes, either. There are no drinks, no chatter, no human bodies, no community

whatsoever, at least from what I can see. I feel partly disappointed, partly like an uncool kid, not invited to the

party, even though the party happened when I was a toddler. The only piercing gaze comes from the amber-yellow eyes of a

pedigree cat, sitting in one of the windows; it probably thought it was me who invaded its space. I approach the cat and

glance inside: natural, beige, neutral, ad nauseam.

I think of this clean and dull apartment and its clinically white walls. Somewhere deep under that whiteness, buried

under several dozen layers of paint, black shapes dance, wiggle, twitch and pulsate, like ancient cave paintings in the

flourishing light of an open fire, despite the artificial, clinical film that shrouded them. I search in Google “Oval

Mansions”, which results in a few house listings for sale. Impatiently I look through photographs of one of the places:

Oh, the irony.